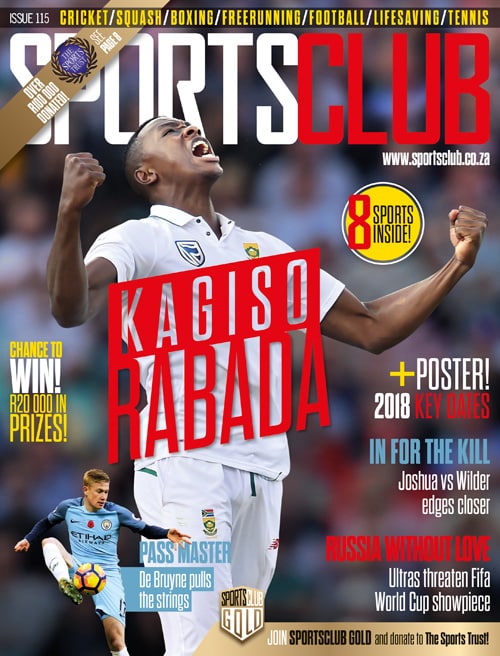

The Proteas have a gem on their hands in Kagiso Rabada, who is now the world’s No 1-ranked Test bowler, but they must handle him with care, writes SIMNIKWE XABANISA in SportsClub magazine.

When legendary boxing trainer Cus D’Amato first laid eyes on a teenage Mike Tyson, he was so taken by him that he went home and told his wife Camille that the boxer he’d been waiting for his whole life had just sauntered into his gym.

What with Dale Steyn still raging against the dying of the light – one 140km/h delivery at a time – D’Amato’s claim might be a contentious one to make for the South African cricket fraternity when it comes to young fast bowler Rabada.

But it’s quite tempting to do that, because if there’s one thing the precocious Proteas fast bowler’s performances have done to date, it has been to drop broad hints that he is at the very least a once-in-a-generation cricketer.

Much like Tyson went on to become the youngest world heavyweight champion in history, ‘KG’ has been racking up some jaw-dropping numbers: the youngest South African to 100 Test wickets; the fifth youngest in the game’s history and the third fastest South African to that number behind Vernon Philander and Steyn.

But one of the overlooked things about D’Amato’s relationship with Tyson is that in the same way the veteran trainer built ‘Iron Mike’ from an insecure juvenile delinquent into the ‘Baddest Man on the Planet’, the pressure he put on him in teasing out that outrageous talent ultimately burned him out by 25.

When D’Amato was alive, Tyson ate, lived and breathed boxing from his early teens. When he died, Tyson basically ate, drank and snorted his fortune away. So, between the obsessing about the sport and his consumption issues, Tyson was an unfulfilled talent.

While the clean-cut Rabada doesn’t strike one as the hedonistic sort, his unquenchable thirst for cricket – and the need to play him in all formats as a result of his ability – could stop him well short of becoming the greatest fast bowler South Africa has produced.

At 22 and having just started his third season as an international cricketer, Rabada should still be learning the ropes. But injuries to Steyn, Philander and Morne Morkel have seen him frequently thrust into the role of leader of the attack.

The fact he has not disappointed when put in that position has created a problem of sorts in that he has all too frequently found himself as the Proteas’ go-to man when he should have been ringside, watching masters like Steyn and Philander deal with the pressure.

When comparing Rabada’s output to Steyn’s after a similar number of games, the Proteas’ over-reliance on the youngster is evident. After 22 Tests, Rabada has bowled 4,063 balls to Steyn’s 4,169 deliveries.

But the catch is, Steyn was a couple months shy of 25 by the time he’d bowled that mountain of deliveries, whereas Rabada is only 22. Further feeding concerns of burnout is the relentless work the youngster puts in behind the scenes in his quest to be the best bowler in the world.

‘The tough thing is getting him away from the nets because he’s so keen to improve,’ says his Lions coach, Geoff Toyana. ‘Too many bowlers are happy to come to practice and bowl from 9am to 10:30am. KG comes in from 9am to 12pm, goes to gym and then comes back for another bowling spell.’

In trying to reassure all cricket-minded South Africans that Rabada’s career is unlikely to be sacrificed at the altar of burnout, recent Proteas fast bowling coach Charl Langeveldt – who knows Rabada as much as anyone after spending two years with him in the national team – inadvertently mentioned another thing he does too much of.

‘He’s the type of guy who the captain can toss the ball to when the chips are down,’ says Langeveldt. ‘When [England all-rounder] Ben Stokes was going great guns in Cape Town, KG kept bowling and went for plenty, but he wouldn’t back off. You want guys who can do that and KG is someone who just wants to bowl.’

That said, Langeveldt was still at pains to go as far as one can by way of guaranteeing that Rabada, whose annual workload now also takes in the IPL, won’t be worked into the ground: ‘While it’s easier to manage the guys at the Proteas, it’s tough to tell them not to play elsewhere, because we’re not going to compensate them for the dollars and pounds they’ll lose by not playing.

‘But we had to have a talk with him and tell him he had to look after himself. At the beginning, we had to explain to him that when you’re on a break you don’t stop working, you have to maintain.

‘We had to tell him that when you go into a series, you can’t do all the work in the week before; you need to work continuously, even if it’s just doing technical stuff from a short run-up. He’s been great about it, because he’s one of those guys who invest in their careers.’

Warming to his task, Langeveldt reveals the qualities that should help Rabada reach relative fast-bowling ‘middle age’: his natural athleticism and a bulletproof bowling action.

‘He’s an unbelievable athlete; he’s the best athlete I’ve ever seen at that age,’ he says. ‘Allan Donald, Dale Steyn, Makhaya Ntini … those guys were great athletes. But KG is way ahead of where they were at the same age.’

Lions conditioning coach Jeff Lunsky backs that theory: ‘They have a good culture of physical training at his old school [St Stithians] because former weightlifting coach Rodney Anthony is responsible for their strength training, so they’re training the right way.

‘He taught them well, so KG came with a good base and I didn’t have to teach him much. He’s not amazingly flexible, fast or strong, but he’s pretty good at all those things. The fact he doesn’t get injured means you can’t fault his flexibility.’

And to drive the point home, Langeveldt goes back to the most reliable thing in Rabada’s defence, his ‘repeatable’ action, which Toyana agrees with.

‘He’s got the perfect bowling action. We worry about him getting injured due to his workload and we have to manage him properly, but his bowling action will always look after him.’

Perhaps interestingly, Langeveldt feels the return to fitness of Steyn, Morkel and Philander is still probably the best way to keep Rabada in one piece: ‘He needs one or two years with the seniors around him to learn a bit more as a bowler.’

While having the older bowlers around would help ease the workload and pressure on him, it would also help him address the remaining weaknesses in his bowling.

‘He hasn’t bowled well on the subcontinent yet and that was also the case in England,’ says Langeveldt. ‘KG’s natural length is suited to bouncy wickets; on lower wickets he needs to bowl fuller and those adjustments will come with time. He’s also struggled bowling to left-handers, something we’ve worked quite hard on by getting him to bowl around the wicket and move the ball away from the left-hander.

‘But the good thing is, [Proteas head coach] Ottis Gibson has been a fast-bowling coach for a long time and brings something different to the party. Maybe he’ll see something else in KG and take him even further.’

– This article first appeared in issue 115 of SportsClub magazine